What Is Basic Income?

Thirty-eight million Americans still live in poverty. An additional 68 million live in economic insecurity.

Despite significant federal spending on anti-poverty programs, poverty and economic insecurity remain defining features of American life.

In the rapidly shifting economy of the past 50 years, progress has become uncoupled from shared prosperity. In the impending volatility of the coming decades, even more Americans are in danger of being left behind by stagnating wages, power asymmetries between employees and employers, mounting wealth inequality, and the specter of job automation.

A basic income is an unconditional, regular cash payment that guarantees a baseline of economic stability to all citizens.

Despite significant variation among proposals, all basic income programs share four key characteristics :

-

Periodic: a recurring payment, as opposed to a one-time grant.

-

Cash: the payment is strictly cash, to be spent however the recipient sees fit.

-

Individual: the payment is made to individuals, not households.

-

Unconditional: the only eligibility criteria to receive the payment is citizenship.

Basic income offers a way to improve the economic safety net, providing a stronger foundation of income security for all Americans, no matter what.

Despite the simplicity and appeal of basic income, as well as mounting positive evidence from small experiments, big questions remain: Is basic income the best use of government funds, or would alternative investments prove more effective? How much is “basic,” and what would be the best way to offset the program’s cost? How might the effects of a national-scale program differ from those that have been demonstrated in small-scale experiments?

Proposals differ on:

-

Whether the payments are "universal" to all citizens, or "targeted" towards those with lower incomes.

-

The amount of income guaranteed by the program.

-

Whether guardians receive additional payments for children.

-

How much of the existing welfare safety net the income would replace.

-

How to offset costs.

Depending on its design, advocates argue a basic income could:

-

Significantly reduce or eliminate poverty.

-

Stimulate growth by redistributing cash towards those who are more likely to spend it.

-

Promote entrepreneurship by decreasing risk.

-

Increase the bargaining power of workers and reduce inequality.

-

Bring about a variety of social benefits, including improved physical and mental health, improved educational and familial outcomes, and reductions in crime.

-

Decrease the bureaucratic inefficiencies of welfare provision by merging patchwork income support programs into a single program.

Skeptics argue that a basic income could:

-

Discourage work and foster welfare dependence.

-

Be prohibitively expensive and irresponsibly spent.

-

Be less effective at reducing poverty than other uses of tax revenue.

-

Cause price inflation.

What does the evidence say?

Effects Basic Income on Growth

Current evidence suggests a number of ways in which basic income might help to grow the economy:

- Putting more money in the hands of those most likely to spend it

- Reducing the risks of entrepreneurship

- Enabling educational and professional investments

- Reducing other welfare expenditures by lifting citizens out of poverty

But to determine the overall impact of basic income, the benefits of unconditional cash must be weighed against the potential costs of taxes used to fund the program, and against the opportunity cost (i.e., sacrifices) of foregoing other potential policy options.

While current evidence cannot answer all questions about basic income, current findings strongly counter two common concerns. They show that, at least in small-scale experiments, receiving unconditional cash does not discourage work. Neither does it cause significant inflation.

Basic income could grow the economy by increasing demand for goods and services and raising long-term earnings through educational and professional investments.

Whether basic income increases aggregate demand for goods and services may ultimately depend on the balance between the redistribution of spending power, and the effects of taxes used to fund the income.

By redistributing money from higher-income to lower-income citizens, basic income puts more money in the hands of those who are more likely to spend it . This is because, in general, as income increases, more of a person’s needs and wants are satisfied, raising their likelihood to save instead of spend additional income. Although this would raise aggregate demand across the economy, the potentially countervailing effects of higher taxes must be considered to determine overall impacts .

Besides increasing aggregate demand, basic income may also lead to educational and professional investments that lead to higher wages in the medium to long term. In California’s SEED pilot program, for instance, receiving basic income enabled recipients to work fewer part-time shifts. Instead, they spent more time searching for better employment , completing training programs and internships, and taking greater risks in search of better opportunities.

In a long-run study of cash transfers, Mexican infants whose mothers received conditional cash transfers showed significant benefits in education, wages, and geographic mobility twenty years later. And across a series of basic income experiments in the US in the 1970s, receiving basic income was associated with an increase in the number of adults pursuing higher education, as well as increased high school completion rates .

Research on the impact of expanding the child tax credit into a child allowance - effectively implementing a basic income for kids - found that the program’s cost of $100 billion per year would be offset by $865 billion in annual monetary and non-monetary benefits . These include $80 billion per year from children’s increased future earnings, and $670 billion from improvements in child health and longevity.

In developing countries, where cash transfer programs are externally funded (without taxation, often through charity), their economic effects on growth are significant and positive. In Namibia, basic income raised the rate of those engaged in “income generating activities” from 44% to 55% . In Mexico, basic income recipients invested 26 cents of every peso in productive assets, raising agricultural income by nearly 10% and raising long-term consumption by 1.6 cents . In Kenya, a one-time cash transfer of $1,000 to over 10,500 poor households led to sharp increases in income and consumption , with roughly 2.6 dollars worth of increased economic activity per dollar spent (and despite the sudden spike in money supply, minimal price inflation occurred).

Econometric simulations of the effects of a US nationwide program produce conflicting results depending on the model’s assumptions. The Roosevelt Institute, using the Levy Model, found that a tax-financed universal basic income (UBI) of $6,000 per year would increase GDP by 1.65% , and that a $12,000-per-year UBI would increase GDP by 2.62% . The Penn Wharton Budget Model, however, which was built with different assumptions, predicts that a tax-financed UBI of $6,000 per year would decrease GDP by 1.7% .

A robust, global body of research finds that receiving unconditional cash does not create dependency or discourage work. However, existing experiments are limited in what they can tell us about the effects of a full-scale, national program. Few experiments have studied higher-level payments in the US.

A 2020 systematic review of 38 empirical studies on the relationship between unconditional cash transfers and basic income in different parts of the world found no evidence that receiving unconditional cash transfers creates dependency or discourages work :

Despite a detailed search, we have not found any evidence of a significant reduction in labour supply. Instead, we found evidence that labour supply increases globally among adults, men and women, young and old, and the existence of some insigificant and functional reductions to the system such as a decrease in workers from the following categories: Children, the eldeerly, the sick, those with disabilities, women with young children to look after, or young people who continued studying.

Regarding concerns that unconditional cash transfers discourage work, the Stanford Basic Income Lab writes: "The evidence from existing UBI related schemes, however, negates many of these concerns and, overall, indicates that UBI-related programs have marginal effects on labor market participation."

The results are especially clear in the developing world. Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee and colleagues conclude, in their paper titled “ Debunking the Stereotype of the Lazy Welfare Recipient,” that they "find no systematic evidence that cash transfer programs discourage work."

In the US, monthly recipients of an unconditional $500 in California’s Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED) obtained full-time employment at more than twice the rate of non-recipients.

Research on the child tax credit - effectively a basic income for the families of children - finds similar outcomes. When President Biden expanded the existing Child Tax Credit (CTC) into an unconditional program with no work requirements, there was no change in recipients’ employment rates. Similarly, research on expanding the CTC finds that a $1,000 increase in the benefit amount is associated with a 0.37 hour , or 1.1% increase in working rates of recipient single mothers. As this and the SEED basic income experiment suggest, receiving unconditional cash may sometimes increase, rather than decrease, employment rates.

One notable exception is a series of experiments with negative income tax ( NIT) – a form of basic income – conducted in the 1970s across the US and Canada. Although initial results found significant reductions in work participation for NIT recipients, subsequent research discovered errors in the earlier methodology . After correcting for the errors, the findings suggested minimal reductions in work participation, in line with findings from more recent studies.

Econometric models - across all assumption bases - predict similarly negligible impacts of a nationwide basic income on employment. The Levy Model predicts a 0.31% increase in employment rate , while the Penn Wharton Budget Model predicts a 3.2% reduction in hours (roughly 1.2 hours) worked by households .

Even if a nationwide basic income did lead to modest reductions in overall working hours, standard economic theory suggests that those hours could be filled by presently unemployed job seekers, tightening the labor market and improving the overall efficiency of the economy.

Basic income could increase entrepreneurship and small business formation by decreasing the risks of failure.

The share of US employment accounted for by young firms has declined by nearly 30% over the past 30 years. A growing body of evidence suggests that more generous safety nets lead to higher rates of entrepreneurship. One rationale is that strong safety nets reduce the risks of failure faced by entrepreneurs .

For example, one study found that expanding access to public health insurance led to a 15% increase in self-employment . Another study on expanding food stamp eligibility found an increase of 12% in new firm incorporation. Notably, in the case of expanded food stamp eligibility, Walter Frick of the Harvard Business Review observed that many of the newly eligible entrepreneurs didn’t enroll in the expanded food stamps program. Instead, "simply knowing that they could fall back on food stamps if their venture failed was enough to make them more likely to take risks."

In France, unemployment benefits were expanded to allow those transferring from unemployment to self-employment to temporarily continue drawing benefits. In addition, the expansion guaranteed that, should their venture fail, they would once again be eligible for unemployment benefits. This expansion to unemployment benefits led to a 25% increase in new firm creation .

Research on the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend ( PFD) found that receiving unconditional dividends boosted entrepreneurship rates , but that the effects dissipated over time. The study’s authors speculated that the gradual decline in the size of the dividends might partly account for the decreasing effect.

Although previous studies have established a negative relationship between overall government spending and entrepreneurial activity, a recent study suggests that what matters is not so much the overall size of government, as the composition of its spending. Given a fixed “pie” of government spending, increasing budget allocation toward social and public goods (such as basic income) relative to private subsidies (such as subsidies to agriculture, energy and fuel, manufacturing, defense spending, and mining) is associated with higher entrepreneurial activity .

Nonetheless, there has been little direct study of how basic income programs may impact entrepreneurship, in part due to the limitations inherent in small pilot programs. Thus, where entrepreneurial growth is concerned, the question of whether basic income would be the most effective expansion of government programs relative to other possibilities—such as universal healthcare, job guarantees, or the expansion of existing programs—remains unclear.

By consolidating various welfare programs into a single basic income, the US could reduce bureaucratic inefficiencies while more effectively reducing poverty.

Despite $361 billion of federal spending on safety net programs in 2019, 34 million Americans remained in poverty.

The US has a variety of overlapping welfare programs, each with different eligibility criteria, benefit amounts, and administrative infrastructures. As a result, inadvertent “poverty traps” are created, disincentivizing low-income workers from increasing their incomes lest they lose more in benefits than they gain in wages.

These various income-support welfare programs could be consolidated into a single basic income instead , reducing bureaucratic inefficiencies and poverty traps, while more effectively reducing poverty.

The U.S. social safety net includes a variety of income support programs that might be replaced by a single guaranteed income policy to the net benefit of current recipients and non-recipients alike.

In European econometric simulations, basic income—whether in the form of negative income taxes or universal basic income— performs better at maximizing social welfare than existing systems of conditional welfare do.

Similarly, in such econometric models, if it is assumed—in line with current research—that redistribution does not discourage work, then unconditional, negative income tax–style programs perform better at optimizing social welfare than programs with work requirements , such as the existing earned income tax credit ( EITC), do.

By lifting citizens out of poverty, basic income could reduce public spending on healthcare, incarceration, and housing.

Money spent on lifting citizens out of poverty often has a fiscal multiplier effect, where every dollar spent returns more than a dollar’s worth of savings.

A Vancouver experiment, for example, gave a one-time transfer of $7,500 to recently homeless individuals. Compared to a control group that did not receive the transfer, the cash recipients saved an extra $8,172 per year of public expenditure by spending fewer nights in homeless shelters.

As mentioned earlier in this report, research on the potential effects of a child allowance (a basic income given to children’s families) found that $100 billion of annual spending on the program would return $865 billion in annual benefits. The majority of these benefits would come from improved child health and longevity. In particular, the public would save $3.5 billion per year in reduced expenditures on children’s and parents’ healthcare costs .

In North Carolina, giving parents an unconditional $4,000 per year reduced arrests for minors by 22%.

There is no evidence - nor theory - that suggests a tax-financed basic income would cause significant price inflation.

The Stanford Basic Income Lab writes:

Most economists do not share the hypothetical concern that a UBI would cause high and general inflation, because there is no reason to assume that a UBI could not be financed by taxes and dividends—which would use money already in circulation, rather than newly printed money. Insofar as inflation does not involve an expansion in money supply, then, a UBI should not lead to high or hyperinflation.

The case of Alaska provides a large natural experiment. The Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend ( PFD) is an annual, unconditional payment of generally between $1,000 and $2,000 per year that has been given to each Alaskan citizen since 1981. Following the introduction of the PFD, Alaska's inflation levels actually declined. In the four decades since, Alaska has experienced lower inflation levels than the US average .

Other findings—from Kuwait granting every citizen $3,600 in celebration of the country's 50th anniversary, to experiments across Mexico, Kenya, and India—also find no inflationary effects associated with cash transfers.

Similarly, no significant inflation is found by econometric models designed to predict the impacts of US nationwide UBI programs. The Levy Model predicts that even a nationwide UBI of $12,000 per adult that is deficit-financed (the most likely funding method to spike inflation) would only raise price levels by 3.77% over eight years. Notably, a simulation of UBI in New York City found that housing prices would actually decrease .

Effects of Basic Income on Stability

The observed effects of basic income are overwhelmingly positive in the areas of education, physical and mental health, crime, family relationships, poverty, and inequality.

This should come as little surprise. Giving citizens more money should produce positive outcomes. Still, the question remains as to whether basic income would be the best approach relative to other possibilities, and how high a payment would be necessary to achieve optimal benefits.

How basic income affects poverty depends significantly on the benefit amount, the financing method, and what happens to existing welfare programs. A benefit amount set at the poverty line could eliminate poverty, but at a significant cost that would require new taxes. A revenue-neutral basic income that simply replaces all other welfare programs would leave the most vulnerable populations words off.

A basic income set at the poverty line would eliminate federally recognized poverty in the US, but at a high cost burden. Smaller programs could still significantly reduce poverty.

In 2021, 82% of Americans were dissatisfied with the nation’s efforts to reduce poverty and homelessness .

A basic income that eliminates poverty could be achieved in at least two ways: a universal basic income with an annual payment equal to the poverty line, or a negative income tax with an income floor set at the poverty line, which then phases out as earned income rises.

One estimate that uses data from 2004 suggests that a negative income tax that fully eliminated poverty would have cost between $219 billion and $336 billion (in 2007 dollars), depending on its phaseout rate. Another, more recent estimate suggests that a UBI set near the poverty line would have a gross cost of around $2.8 trillion per year .

Smaller basic incomes could still substantially alleviate poverty. A basic income of $250 per month ($3,000 per year) given in full to all households that earn less than $150,000 per year is estimated to reduce poverty by 45% and childhood poverty by 65% .

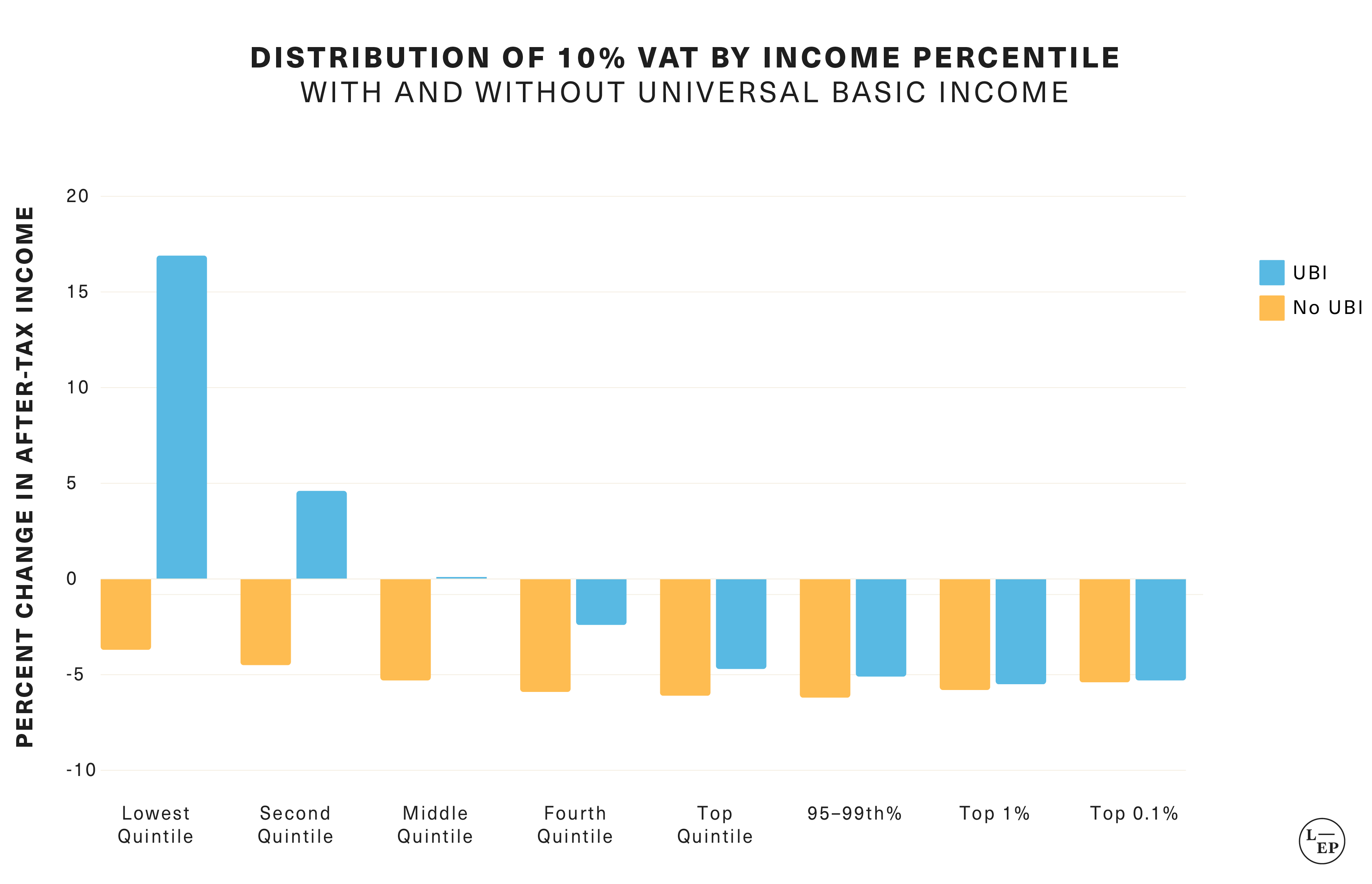

Estimates also find that raising money with a 10% value-added tax and disbursing the revenue to all citizens in the form of a UBI set at 20% of the poverty line, or $2,500 per year, would progressively benefit the incomes of the bottom 60% of the population .

Findings on inequality from Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividends are mixed. Some research finds that distributing the unconditional payment to all citizens reduced inequality . Others found that in the long run, it may increase inequality if wealthier recipients invest the dividend in higher-yield assets , while lower-income recipients spend the payment on goods and services.

Simply scrapping all existing welfare programs and repurposing the funding towards a basic income would leave the poor, parents, the elderly, and the disabled worse off.

Varieties of basic income proposed by Milton Friedman or, more, recently Charles Murray are conceived as full replacements for the entire welfare state. This is known as a “pure UBI.” This kind of revenue-neutral swap of the welfare state for an equivalent basic income would disproportionately benefit the childless, young, and nondisabled , thus benefiting the middle class more than the most vulnerable or lowest-income groups.

The same pattern prevails in the UK. A UBI that replaces all other means-tested benefits would benefit the middle class more than lower-income groups , and would increase poverty rates for children, pensioners, and working-age adults .

But when a basic income replaces only some benefit programs, leaving others in place, the basic income might fare far better than alternative options. For example, studies find that a UBI would have potential advantages over both unemployment and the earned income tax credit .

When thinking about how to draw the line between what should remain and what should be replaced, two considerations prove helpful. First, basic income is a more effective program in well-functioning markets. Basic income is a poor tool in industries with underlying market problems, whether these problems be information asymmetry, externalities, or barriers to entry .

Second, we can draw a distinction between welfare programs that serve an “insurance” function and those that serve an“income support” function. In theory, basic income could provide a stronger replacement for all income-support welfare programs (such as the earned income tax credit, or temporary assistance for needy families). However, basic income would be a poor replacement for welfare that serves a public insurance function (such as unemployment, or healthcare).

Basic income recipients report significant gains in mental health.

Basic income may significantly improve mental health by raising the baseline of economic security. Beyond being a material deprivation, poverty is a psychological deprivation, creating psychological feedback loops that perpetuate poverty.

Among both the employed and unemployed, expectations of future economic insecurity significantly reduce mental health (up to 0.18 standard deviations from the mean) . These expectations of future economic insecurity are more detrimental to mental health than actual, realized episodes of economic insecurity. In particular, fear of unemployment is the most damaging form of economic insecurity . A basic income would raise the income floor, alleviating the depths of perceived future economic insecurity.

In California, results from the SEED experiment find that basic income recipients experienced clinically significant gains in mental health . In Kenya, a one-time unconditional transfer equivalent to $1,076 had greater positive impacts on psychological wellbeing than a five-week psychotherapy program . In India, among low-income workers who received extra cash transfers, mistake rates declined and productivity rose by 6.2% , which the study authors attribute to the psychological benefits of alleviating financial concerns.

Some studies even find that by reducing mental stresses, unconditional cash transfers reduce addictive behaviors such as alcohol and drug use and gambling .

In a nationwide experiment in Finland, recipients of basic income over a two-year period reported improved mental health and cognitive function. The researchers described the recipients’ experiences as follows:

They were more satisfied with their lives and experienced less mental strain, depression, sadness, and loneliness. They also had a more positive perception of their cognitive abilities, i.e. memory, learning and ability to concentrate. In addition, the respondents who received a basic income had a more positive perception of their income and economic wellbeing than the control group.

The basic income recipients trusted other people and the institutions in society to a larger extent and were more confident in their own future and their ability to influence things than the control group. This may be due to the basic income being unconditional, which in previous studies has been seen to increase people’s trust in the system.

Finally, a global meta-analysis of the effect of cash transfers on self-reported mental health found significant benefits in low- and middle-income countries , with an average effect size of 0.1 standard deviations.

Receiving basic income is associated with improvements in physical health, reductions in crime rates for minors, higher educational attainment, and improved familial relationships.

In Dauphin, Canada, recipients of basic income had an 8.5% decrease in hospitalization rates relative to control groups. In Alaska, each additional $1,000 in unconditional dividends from the Alaska Permanent Fund decreased the probability of an Alaskan child being obese by as much as 4.5% , and the dividends overall were associated with reductions in low birth weights .

In US basic income experiments in the 1970s, receiving basic income was associated with improved infant health . When the US subsequently reformed its welfare programs to make cash transfers conditional upon work, infant mortality rates went up, in particular for foreign-born Mexican women .

Basic income experiments taking place across Seattle and Denver found that receiving basic income increased the number of adults pursuing continuing education; raised high school completion rates by 25%–30% , and improved attendance, grades, and test scores, especially for children of low-income households . In North Carolina, children of low-income households receiving an unconditional $4,000 per year increased their educational attainment .

Implementation

When implementing basic income, details are crucial. One reason the idea enjoys such bipartisan interest is because slight changes in its design can significantly change the kind of effect the program has.

Basic income may cost anywhere from $219 billion to $3.4 trillion per year, depending on whether it’s universally given to all or targeted toward those with lower incomes, whether parents get extra cash for children, and how much the payment actually is.

There is not enough research on the optimal payment amount. Neither is there enough research on the opportunity cost of larger basic income programs. Both universal and targeted programs achieve similar outcomes, but each carries unique positives and negatives.

Although the costs of smaller programs would be relatively simple to offset, larger programs would require new or higher taxes, increasing the challenge of political feasibility.

Basic income could cost anywhere from $219 billion to $3.4 trillion annually depending on the details of its implementation.

Negative income tax programs have a single cost that generally ranges from $219 billion to $1.09 trillion depending on benefit amounts, phaseout rates, and whether minors are included.

The relevant costs of universal basic income programs are twofold, with both a gross cost (the total amount of money distributed) and a net cost (the total amount of money distributed, minus the revenue from additional taxes that fund the program).

The gross cost of a $12,000-per-year UBI is estimated between $2.8 trillion and $3.4 trillion annually, depending on the adult population size. The net cost of UBI proposals depends on the specific taxes used to fund the program, but current estimates range from $539 billion to $1.69 trillion .

Here is a sampling of real implementation proposals across a broad range of costs and approaches:

Wiederspan, Rhodes, and Shaefer’s household negative income tax

Features: Goes to households, eliminates poverty (set at 100% of the poverty line) and phases out completely by 303% of the poverty line (33% phaseout rate).

Gross/net cost: $336 billion per year (for calendar year 2004, using 2007 dollars. $482 billion in 2021 terms).

Hartley and Garfinkel’s Small Guaranteed Income

Features: $250 per month to all individuals aged 64 and below. Begins phasing out once individual income surpasses $150,000.

Gross cost: $720 billion

Kirwan Institute Guaranteed Income

Features: Payment of $12,500 to all individuals earning $0, begins phasing out once earned income surpasses $10,000, and phases out entirely once single-adult households earn $50,000. Includes additional support of up to $4,500 per child.

Gross cost: $876 billion per year.

Andrew Yang's Freedom Dividend

Features: $1,000 per month to all adults.

Gross cost: $2.8 trillion.

Charles Murray’s Pure UBI Proposal

Features: $10,000 to every adult, plus $3,000 for catastrophic healthcare. Replaces all welfare transfers.

Gross cost: $2.023 trillion (in 2002 dollars).

Net cost (minus taxes): $1.74 trillion.

Net cost (minus taxes and transfer replacements): $355 billion.

How could we pay for basic income? Common financing options for smaller programs include consolidating income-support welfare programs, closing tax credits and exemptions, and stronger tax enforcement. Larger programs would require additional taxation. Commonly cited options range from value-added taxes to carbon or land value taxes.

The cost of smaller basic income programs, such as Wiederspan, Rhodes, and Shaefer's negative income tax, can be covered by consolidating existing welfare programs, closing tax credits, or stronger tax enforcement.

In 2019, the government spent $361 billion on income-support welfare programs ( $217 billion on the EITC, TANF, SNAP, and SSI alone ), most or all of which could be consolidated into any basic income proposal. Recent estimates suggest that the tax gap - the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid - totals roughly $600 billion annually . The Treasury Department estimates that spending an extra $80 billion in IRS funding over ten years could generate an extra $320 billion in tax revenue. A further $460 billion could be raised over the next decade if data sharing between the IRS and financial institutions were implemented.

The cost of moderately more expensive programs, such as Hartley and Garfinkel's $250-per-month guaranteed income, can be mostly covered by closing existing tax credits that disproportionately benefit the already wealthy. The remaining cost can be other means, such as stronger tax enforcement or, as Hartley and Garfinkel propose, a carbon tax.

Larger programs, such as the Kirwan Institute's proposal or Yang's Freedom Dividend, would require all of the above, plus larger, broad-based taxation, to cover their cost. The most common type of broad-based taxation would be a value-added tax, which as of 2018, has been in effect for all OECD countries except the US. It is also in effect for 166 of the 193 countries with full UN membership. Estimates are that a 10% value-added tax in the US (half the average rate in Europe) would raise an average of $1 trillion per year .

Other taxes proposed as funding sources for basic income include carbon tax, land value tax, consumption tax, payroll tax, wealth tax, and financial transaction tax.

One final way to offset program costs is to account for the expected economic growth caused by basic income, as well as reductions in public expenditure, such as reduced rates of incarceration, healthcare expenditure, and welfare use. For example, Vancouver's cash transfer of $7,500 to recently homeless individuals more than made up the entire program cost by reducing the nights that recipients spent in homeless shelters, which reduced the necessary public funding.

Along similar lines, one estimate found that implementing an unconditional child allowance that costs $100 billion per year could generate up to $865 billion per year in monetary and non-monetary benefits—again, more than offsetting the program’s full cost. Reducing childhood poverty could also spur economic growth that offsets program costs in the long run. Childhood poverty is estimated to cost the United States $500 billion per year , and is furthermore estimated to reduce productivity and output by 1.3% of GDP , raise the costs of crime by 1.3% of GDP , and raise the costs of healthcare expenditure by 1.2% of GDP.

Should we have basic income for all, or target it toward lower-income groups? Universal programs are simpler and more effective, but require more revenue. Targeted programs have a greater administrative burden and perpetuate welfare stigma, but are more politically and economically palatable, largely because they require less funding.

Counterintuitively, universal and targeted basic income programs can be identical in the extent to which they redistribute wealth , and this is because of the way they are financed. Regardless of whether a program provides a universal transfer to all citizens financed by a flat tax, or a targeted transfer that gives a full amount to low-income citizens and phases out as earnings rise, the amount of money that is being redistributed can be the same.

By way of comparison, UBI can be described as a "pay now, tax later" approach to basic income, whereas NIT is a "tax first, pay after" method.

Nonetheless, there are significant differences between the UBI and NIT approaches to a basic income.

Universal programs are easier to administer, more popular among citizens , and more highly correlated with higher levels of redistribution than means-targeted programs . But they require roughly double the level of funding to achieve similar outcomes , which some argue reflects a greater strain on society’s overall ability to redistribute wealth effectively .

Means-tested programs like NIT require fewer taxes to achieve identical redistributive effects. However, they require complicated administrative systems to match benefit payments to fluctuating incomes. They also create incentives to underreport income, create administrative frictions (such as the additional time individuals must spend reporting their income) that may keep the most vulnerable from receiving benefits, and perpetuate welfare stigma.

In a series of NIT experiments across the US in the 1970s, recipients consistently underreported their incomes in order to receive higher benefit payments. A national NIT program could face similar reporting issues.

How much should basic income pay? There is not enough research identifying the most effective amount or weighing the opportunity costs.

Some advocates argue that a just society ought to provide the highest sustainable basic income to all citizens , while others argue that the payment should be just high enough to meet an individual’s basic needs. By unconditionally providing for every citizen’s basic needs, basic income could ensure that all participation in the labor market is truly voluntary , by virtue of maintaining a real alternative.

But how much is necessary to meet a citizen’s basic needs? Higher basic income proposals take the poverty line as a rough approximation. But any program large enough to provide a minimum income of the poverty line to all citizens would carry significant opportunity costs.

What “opportunity cost” means is that every dollar spent on basic income is one that could be spent on something else. As such, to weigh opportunity costs means to consider the fact that there is likely a point after which increasing the basic income amount does less good than allocating funds to other kinds of programs. But as the Jain Family Institute writes, there is insufficient research to identify this threshold :

...for a given budget constraint, each dollar disbursed on a guaranteed income is one not spent on other necessary programs, so it is reasonable to ask about cost-effectiveness: what is the optimal benefit amount from a cost-benefit perspective? At what point ($3600/year? $7200/year? $12,000/year?) do decreasing marginal impacts per dollar disbursed suggest that the money may be better spent elsewhere? Here again, evidence is limited as there are few studies that directly compare the impacts of different transfer amounts.

Current research measures a hypothetical basic income against the current reality of welfare programs, which are largely means-tested welfare programs like the EITC. There is little research that compares basic income against other hypothetical programs, which could range from job guarantees, expanded EITC programs, and universal health insurance, to further investments in housing, education, or public services.

Should basic income payments be disbursed once a year or once a month? Larger annual payments tend to be spent by recipients on larger investments, while more frequent monthly payments help to reduce income volatility and diminish debt.

The frequency of payments will likely affect patterns of consumption, savings, and well-being. Because the ideal frequency might vary with individual circumstances, current research is exploring the feasibility of offering recipients a choice .

In research conducted on the earned income tax credit, more frequent payments were found to reduce stress, diminish debt, and improve mental health .

Meanwhile, evidence from Kenya suggests that larger, lump-sum payments tend to be spent by recipients on large assets, while more frequent payments lead recipients to engage in a better balance of spending and saving .

Together with the question of how much basic income should pay and a comparison against alternatives, determining the best frequency of payments could benefit from further research.