What Is Codetermination?

Most American workers have little say in the workplace, leaving them powerless in workplace decisions that govern their everyday lives.

In the modern American corporation, workers have no say in decision-making processes. Control over a corporation’s governance—how to spend its profits, how to mitigate recessions—lies in the hands of owners, shareholders, and executives, and those decisions are guided by the directive to maximize value for shareholders.

For as long as the doctrine of maximizing shareholder value (MSV) has dominated corporate governance, executive pay has soared relative to workers’ , and the bargaining power of workers has continued to decline. Businesses have also begun reinvesting less of their profits back into the business , opting instead for practices such as stock buybacks and dividends over those of capital reinvestment, research and development, or raising wages.

Codetermination would give workers the right to vote by mandating that a portion of seats on decision-making boards of large companies be held by worker-elected representatives.

Just as constituents of a given district elect representatives to reflect their interests in the public decision-making process, workers would democratically elect representatives to the corporate boardroom who would hold decision-making power alongside the representatives of company shareholders.

Codetermination, which is already common across major European countries, enjoys broad support among Americans , including majority support in every state . It is an application of economic democracy that has the potential to address a broad array of issues, including boosting worker power, improving the flow of information within firms, redirecting business investment towards more productive and less extractive ends, and mitigating the negative effects of corporate power on the democratic process .

But what works in Europe would not necessarily work in the United States. Questions remain as to whether codetermination would be a good fit for the American economy. Would giving workers voting power create gridlocks in corporate decision-making that stifle the American economy’s dynamism and innovation? Could there be more effective ways of enhancing workers’ bargaining power?

Proposals differ on:

-

The percentage of corporate board seats to be held by worker representatives.

-

The eligibility criteria determining which companies are subject to the mandate.

Advocates argue that codetermination could:

-

Help transition our economy from a "shareholder" economy to a "stakeholder" economy.

-

Strengthen our commitment to democracy by extending democratic principles into the workplace.

-

Reduce the disparity between worker and executive pay.

-

Reduce the rate of stock buybacks and dividends, redirecting profits towards more productive allocations.

-

Reduce information asymmetries between employers and employees, which would improve efficiency and productivity, strengthen trust, and create more adaptive and competitive firms.

-

Raise job satisfaction and improve working conditions.

Skeptics argue that codetermination could:

-

Give workers too much power, reducing capital investment and leading to inefficient over-investments in worker benefits.

-

Create friction and inefficiencies in corporate decision-making that ultimately reduce firm performance.

-

Be affected by American corporate governance laws such that the benefits of codetermination are dampened and the negative consequences amplified.

-

Undermine the innovation that drives American economic dynamism.

What does the evidence say?

Effects of Codetermination on Growth

Most recent studies of European codetermination are converging on a surprising finding: codetermination appears to have little impact, positively or negatively, on firm performance.

Although some studies suggest positive impacts in areas ranging from capital formation to productivity, their authors stress that such positive findings are tenuous.

Instead, many advocate the absence of negative effects: Why not try codetermination if it can extend our valued democratic principles to the workplace while doing no harm to the economy?

Workers and executives across Europe have had positive experiences with codetermination, suggesting that decision-making gridlock would not be a concern.

But the European economic landscape is significantly different from the United States’, and we should not assume the European experience would be replicable in the US. Some argue that codetermination would harm American dynamism, while others argue that America’s meager network of labor institutions relative to Europe’s suggest we might mean that the US would experience larger effects, whether positive or negative.

Recent studies suggest that European codetermination has had no negative economic effects. In some cases, small positive effects have been observed.

Across a variety of existing studies, most agree that European codetermination has had no negative impact on the economy . While there are tenuous suggestions that codetermination may have minor positive effects, the consistent absence of negative effects is the more prominent finding.

In Germany, studies found that codetermination had no significant influence on stock prices , profits , or workers' wages . Nor did the threat of codetermination deter German firms from incorporating .

In Finland, codetermination had no negative effects on profitability or firm survival rates . Nor did Finnish firms attempt to avoid being subject to the codetermination laws , such as by changing their firm size to remain below the threshold of 150 employees that determines what companies must comply with codetermination. In fact, Finnish codetermination is associated with a slightly positive effect on capital formation (the overall accumulation of capital assets such as equipment, tools, transportation, or other physical assets).

In Sweden, only 5% of corporate directors reported that codetermination had a negative impact on company activities .

Overall, according to a 2021 survey paper,

"The available evidence indicates that the European model of codetermination is neither a panacea for all of the problems faced by 21st-century workers, nor a destructive institution that is dramatically inferior to shareholder primacy. Rather, as currently implemented, it is a moderate institution with, on net, nonexistent or small positive effects."

A rising chorus of voices are therefore beginning to suggest that, on the basis of the latest evidence, codetermination does not appear to have any negative economic effects. Earlier studies did, however find potential negative impacts.

A study from 2000 (updated 2021) found that relative to firms with one-third codetermination, firms with equal codetermination (half of corporate board seats held by worker-elected representatives) had a 26% decline in market-to-book ratio . In equal-codetermination firms, employees used their power to increase employees-to-sales and wage-bill-to-sales ratios , suggesting a resistance to firm restructuring.

In 1993, one of the earliest attempts to quantify the economic effects of codetermination found strong negative economic consequences following the enactment of Germany’s 1976 laws, which increased the portion of supervisory board seats held by worker representatives from one-third to half. These findings included declines in profitability, productivity , and return on shareholder equity .

Passing codetermination laws in European countries is associated, cautiously, with higher productivity

A 1982 survey of empirical work on employee participation in management concluded:

There is apparently consistent support for the view that worker participation in management causes higher productivity. This result is supported by a variety of methodological approaches, using diverse data and for disparate time periods.

Since then, however, studies have generally found either no effect or modest positive effects on productivity.

In Germany, codetermination increased labor productivity (value added per employee increased by 16%–21%), but had no effect on total factor productivity. In particular, the 1976 strengthening of the laws, which increased the portion of seats held by worker representatives from one-third to half, had a small but positive effect on productivity .

In Finland, codetermination is associated with both small increases in labor productivity and a small increase in total factor productivity .

In France, a study comparing labor-managed and conventionally managed firms found that firms owned and managed by workers are generally at least as productive, if not more so, than their conventional counterparts . Labor-managed firms may even use their technological inputs more efficiently .

In European countries, codetermination has neutral or mildly positive effects on wages. But in the American context, where workers have less bargaining power to begin with and more to gain, the effects may be larger.

Codetermination could affect wages in at least two different ways: raising the wage bottom by giving lower-income workers more bargaining power to negotiate higher wages, or lowering the top, since workers with voting power are less likely to approve exorbitant executive compensation and bonuses.

In European, such wage effects of codetermination appear to have been either minimal or not materialized at all. In Germany, codetermination had no effect on raising the lowest wages . In Finland, codetermination raised wages slightly for the lowest earners within firms , mildly reducing overall wage inequality.

In Norway, broad findings suggest that adopting codetermination had no direct impact on wages. Although workers at codetermined firms are paid more and face less earnings risk , these effects more likely stem from other factors correlated with codetermination , such as larger firm size or higher unionization rates:

...while employees do benefit from working in a firm with worker representation, the gains are not driven by worker representation per se, but rather by other factors that are correlated with both worker representation and worker compensation.

But, in countries such as the US, where workers have significantly less bargaining power than in European countries, codetermination may have a stronger effect on wages. In the US, workers at employee-owned businesses receive 5%–12% higher wages than workers at traditionally owned companies, have twice the retirement accounts, and are 25% less likely to be laid off .

Existing evidence does not support the concern that codetermination may lead to decision-making gridlock. In Europe, executives and workers alike report positive experiences, unimpeded decision-making, and improved relations.

One criticism of workplace democracy—which codetermination helps to implement—is that it might introduce the same gridlock that plagues the legislative branches of many democratic governments, that of the United States in particular.

But evidence from abroad would seem to alleviate this concern. The European experience with codetermination suggests that the structural arrangement it implements has aligned the interests of workers and management and built empathy across stakeholders . By improving the communication of information between workers and managers (also known as reducing information asymmetry), codetermination may even boost growth.

In Germany, a 1998 commission unanimously concluded that codetermination improves information flow between management and works, deepening trust between them. Furthermore, a study of German innovation under codetermination found that an "overwhelming majority" of codetermined supervisory board decisions were unanimous . It concluded that there was no evidence that codetermination reduced innovation, and that there might even be a positive relation between them .

In Sweden, where union participation and codetermination are closely related, 86% of managing directors reported that union participation did not contribute to conflict or slowing down of company operations, and 76% of corporate directors reported positive experiences with codetermination. Only 5% of corporate directors reported that codetermination had a negative impact on company activities.

Laws on codetermination... have made European CEO’s deeply committed to their employees, treating them more like partners in a long-term enterprise than anonymous factors of production.

Some limited evidence suggests that codetermination may have either a neutral or positive effect on innovation.

One concern about codetermination in the US is that it would stifle the innovation that makes the American economy so dynamic. The concern is that, by granting worker-elected representatives voting rights, a firm’s decision-making process might grow increasingly contested, slowing overall activity.

In Europe, recent studies do not support this concern. Studies of German codetermination found strong evidence for a positive relationship between codetermination and innovation. A study spanning the US, UK, India, France and Germany of how legislation for employee representation affected innovation also found a positive association between employee representation and innovation .

Practically speaking, it is reasonable to imagine that codetermination might slow innovation by creating more friction in the decision-making process, introducing more gridlock between labor and management. Overall, however, the European experience reports that codetermination avoids gridlock while improving information flow, ultimately enhancing the decision-making process.

And in 2018, the World Economic Forum ranked Germany as the world’s most innovative economy, beating out the US in second place.

That said, how much of the prospective American experience with codetermination might be inferred from European experiences is unclear, and we have little direct evidence from which to project the potentially unique effects of codetermination on the American economy.

Increasingly, a large proportion of corporate profits are being invested in stock buybacks and dividends—a shift away from more traditional, productive investments. By granting voting power to workers, codetermination could provide a checks-and-balances system against such “short-termism,” rebalancing corporate investment towards investments that benefit all stakeholders, not just shareholders.

In the US, some advocates of codetermination see it as a guard against “short-termism,” or the tendency to prioritize short-term profits for shareholders over longer-term investments. Codetermination could empower workers to function as a check against executives seeking to repurchase shares, a practice known as stock buybacks.

Buybacks have been widely criticized for drawing significant funds away from capital investment , workplace improvements, wages, and research and development. Although buybacks may have a role as part of efficient corporate strategy , an analysis by SEC Commissioner Robert Jackson finds that buybacks are instead often exploited by executives for personal gain .

Stock buybacks in the US have skyrocketed since 1982, when regulatory limits on open-market share repurchasing were lifted . In 1981, S&P 500 companies spent 2% of profits on buybacks. By 2017, they were spending 59% . Between 2015 and 2017, companies in the restaurant industry spent 136.5% of net profits on stock buybacks , suggesting that they financed buybacks through debt or cash reserves.

Even though one should keep in mind the disparities in scale between the US and Germany’s economies when considering comparisons between them, Germany—where codetermination is in place—had 210 stock buybacks between 1998 and 2014, compared to 11,096 in the US over the same time period.

The rise of buybacks in the US is strongly associated with our heavy reliance on stock-option-based compensation. Firms that rely more on such compensation packages are significantly more likely to repurchase shares . When executives receive stock options as part of their compensation package, the total number of company shares increases, diluting their value. Stock buybacks are often used to counteract this dilution , by reducing the overall number of available shares. Giving workers voting rights—on matters including stock buybacks—could serve as a check against relying too heavily on these practices if they draw too much capital away from ends that benefit a broader group of stakeholders.

In March 2016, Laurence Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, wrote the following in a letter to the executives of S&P 500 firms:

“...in the wake of the financial crisis, many companies have shied away from investing in the future growth of their companies. Too many companies have cut capital expenditure and even increased debt to boost dividends and increase share buybacks.”

As recent research suggests a positive relationship between political democracy and growth, advocates suggest the same relationship may exist between economic democracy and growth. To date, however, there is little research on the direct effects of economic democracy on GDP.

Orthodox theory and evidence suggested that political democracy and growth are in tension. Recent empirical evidence finds the opposite: there exists a positive and significant correlation between democracy and future GDP per capita . The authors find that democracy may encourage growth through economic reforms, increasing human capital, increasing investment, and reducing social unrest .

Advocates suggest these same mechanisms may encourage a positive relationship between economic democracy and growth, especially in the realms of productivity, human capital, and job satisfaction , though we have scant empirical evidence to support the hypothesis.

Effects Codetermination on Stability

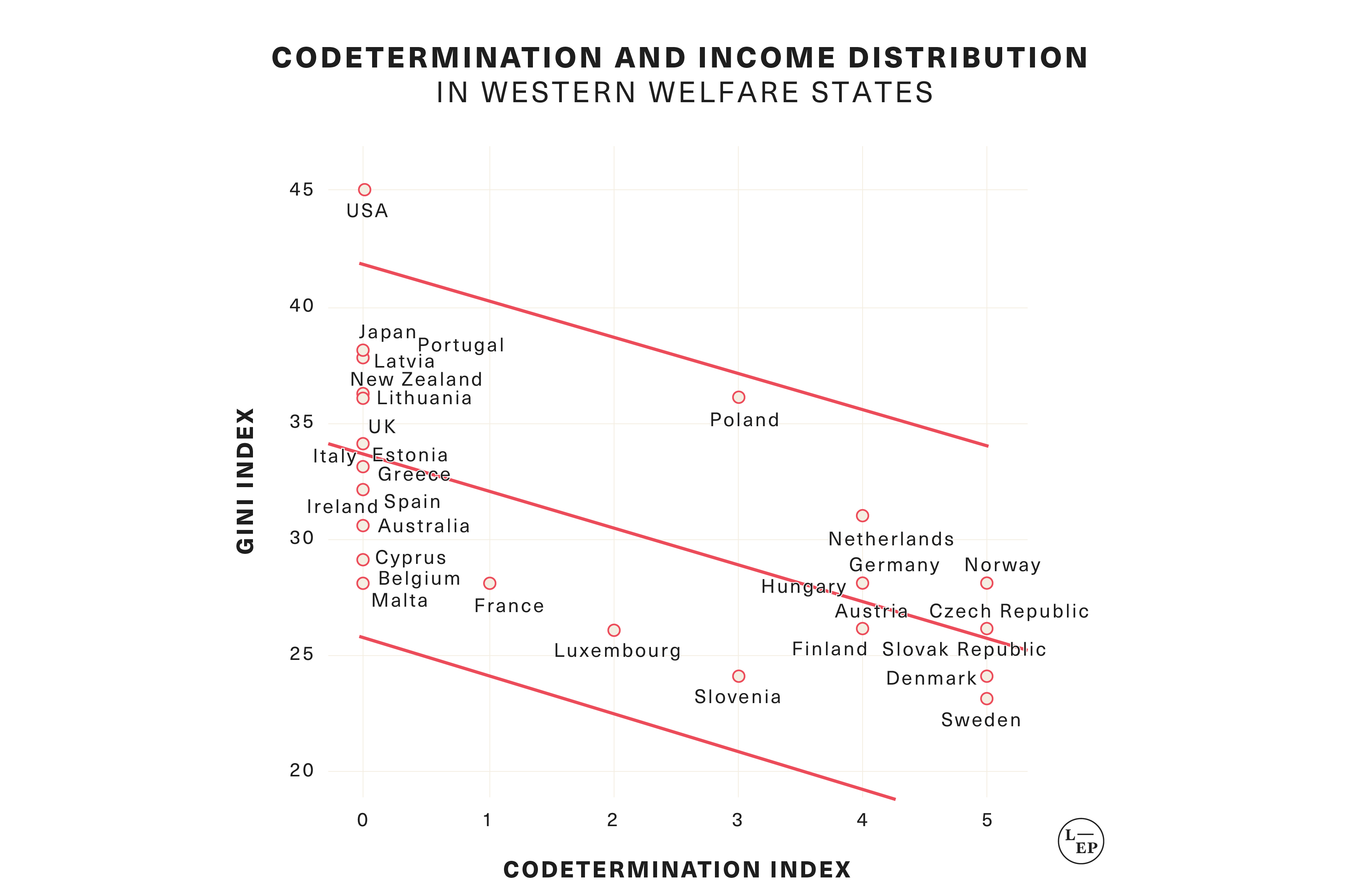

European codetermination has proven to be a remarkably stable practice, and is credited with improving relationships and information flows between workers and managers. Although codetermination is associated with only small increases in wages for low earners, it correlates with the shrinking of income inequality via reductions in the income share of top earners.**

In the US, codetermination offers one strategy for mitigating the effects of concentrated corporate power on democratic institutions. Importantly, a majority of the American people want codetermination.

Understanding codetermination solely as an instrument to protect employees or to improve corporate governance and/or performance fundamentally underestimates its potential contribution to society.

Across the EU and OECD countries, codetermination is associated with reductions in income inequality, and reductions in the highest incomes. But it’s unclear whether codetermination is a causal mechanism, or merely correlated with related factors such as firm size and unionization rates.

Across EU and OECD countries, higher levels of codetermination are correlated with reductions in income inequality . Specifically, decreases in the income share of top earners . Across EU countries, codetermination has a stronger correlation with reductions in national income inequality than with trade union density .

As before, although comparisons between Germany and the US must take into account their disparities in economic scale, some researchers point to differences between the two as evidence of how codetermination may help balance inequality and short-termism. In 2015, the typical German CEO made $5.6 million, while their US counterparts made $14.9 million . Additionally, stock options comprise 24% of average German CEO pay, while in the US, they comprise 63% .

Codetermination has either neutral or mildly positive impacts on wages in Europe. But since codetermination arose in European countries that already had strong worker institutions, we might expect stronger wage effects in the US, where worker institutions are significantly weaker.

The amount of voting power conferred by codetermination matters, and it varies by country. In Germany, where codetermination confers the most voting power, a study found that codetermination had no impact on the lowest wages .

In Finland, where codetermination confers less voting power, wages for the lowest earners rose by roughly 5%–7% , reducing overall wage inequality within firms, but executive compensation remained unchanged .

Finnish worker representatives also reported f eeling powerless to affect company decisions regarding wages.

In Norway, workers at codetermined firms experience higher wages along with less earnings risk during recessions . But the cause of the positive correlation between codetermination and wages appears to be related factors such as firm size and unionization , rather than codetermination itself.

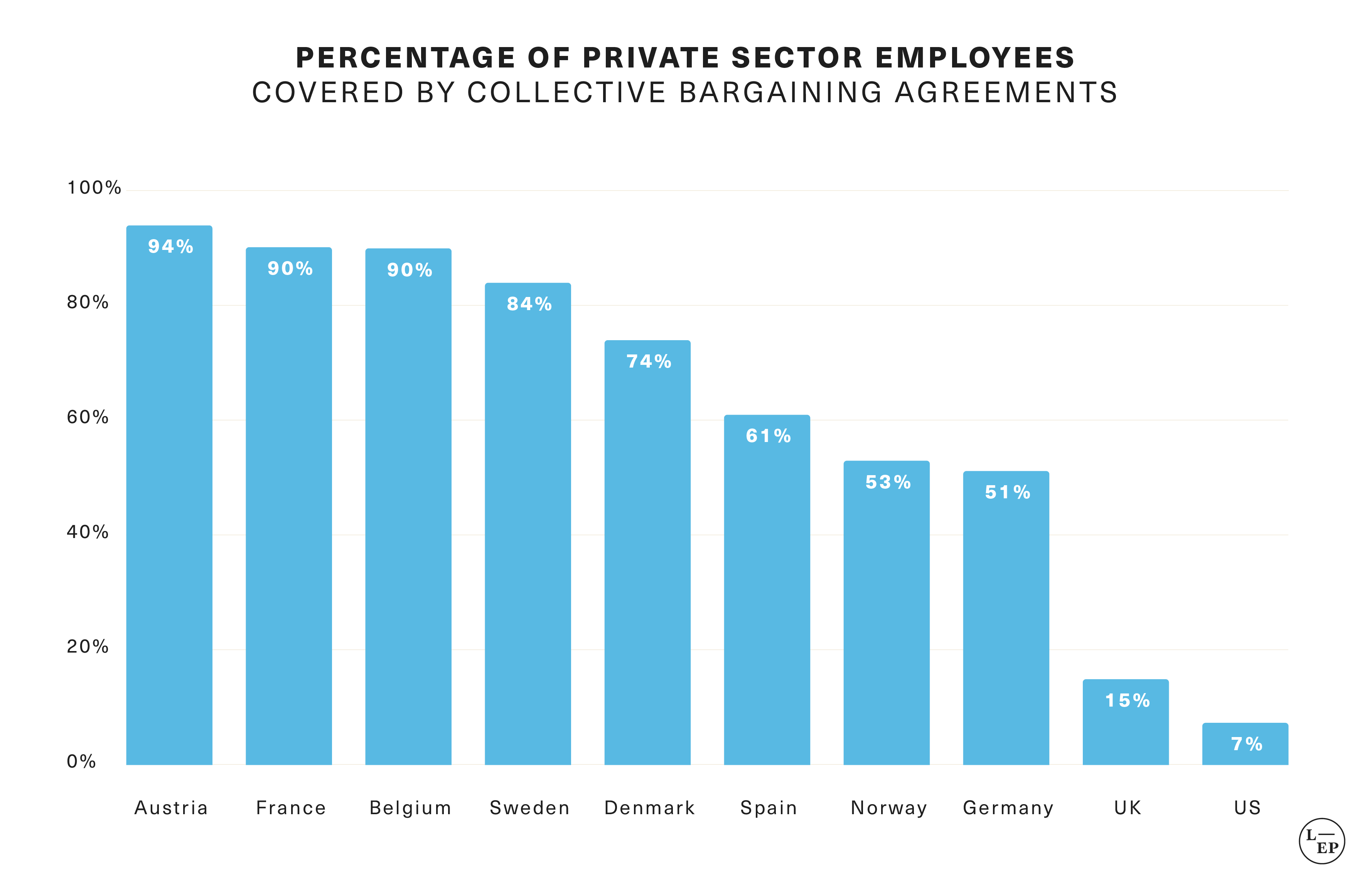

Importantly, we should not assume that codetermination would affect American and European wages in the same way. European countries with codetermination laws had significant preexisting pro-worker institutions, ranging from centralized collective bargaining to high union coverage. Much of codetermination’s potential impact on wages might therefore have already been previously brought about by these institutions.

Several important labor market institutions—sectoral collective bargaining, widespread union representation, and extensive regulation—may already capture most of the low-hanging fruit when it comes to affecting worker outcomes, leaving little room for German and Nordic codetermination to make an impact. If this explanation is correct, then codetermination may have larger impacts (either positive or negative) if implemented in contexts like the United States, where these institutions are less powerful...

In 2015, only 7.2% of US private sector workers were covered under collective bargaining agreements , compared with 50.2% in Germany and over 80% across the rest of Western Europe . In the US, union membership covered a third of Americans in the 1950’s, but had declined to 10.7% in 2021. Given the lack of other channels for bargaining power in the US, codetermination may have more pronounced effects here.

So how might codetermination affect wages in the US? One reference point is worker-owned cooperatives in the US, where employees receive 5%–12% higher wages, have twice the retirement accounts, and are 25% less likely to be laid off .

Abraham Shuchman deduced long ago: "[Codetermination could] mark for the people of the world a new course between capitalism and collectivism that leads to a more rational and more just social order." With regard to the twenty-first century, such an outstanding historical relevance cannot be (undisputedly) attributed to codetermination. However, codetermination may possibly contribute to an increasingly socially defined regime, with regard to distributive justice in form of a more equal distribution of incomes.

Codetermination is associated with slight positive effects on job satisfaction.

In theory, codetermination is expected to raise job satisfaction. In practice, however, job satisfaction is difficult to measure , and requires data to be collected over long periods of time. A survey of Finnish workers suggests that implementation of worker representation slightly improved workers’ perceptions of the quality of their jobs .

A 2021 survey of the existing evidence concluded that overall, codetermination might be associated with either nonexistent or slight improvements in job satisfaction and other elements of worker welfare.

In the US, a nationally representative survey in 2020 found that Americans prefer to work at democratic firms because they intrinsically value having more power in the workplace . The prospect of codetermination raises the probability of employees preferring to work at a firm by 7% , and Americans report that they value economic democracy equivalently to a wage increase of $20 per hour.

The amount of power that codetermination grants workers depends on policy details, such as the portion of seat on the board to be held by worker representatives. Across Europe, existing codetermination laws grant workers a minority voting position, limiting their power.

Most existing codetermination mandates grant a minority share of voting rights to worker representatives, meaning that they can be overruled by united shareholder votes. Even in Germany, where workers at large corporations hold 50% of supervisory board seats, shareholders receive a tie-breaking vote.

A 2021 survey of codetermination across the EU found that existing codetermination laws give workers variable amounts of power in three areas of governance : moderate influence over working conditions, minor influence in layoff decisions, and minor influence over wage setting.

There is “ nearly unanimous agreement that worker representatives have no influence on broad strategic decisions, even when they sit on company boards .” Fewer than 5% of Finnish worker-representatives believe they can affect strategic decisions. Instead, worker-representatives feel that such decisions are made away from their view, and presented only once management’s mind is already made up. 76% of worker representatives say worker representation feels like a formality, and 65% believe the rights of worker representatives are too narrow .

The qualitative evidence paints a picture of an institution that gives workers some control over their immediate working conditions, but grants them negligible authority beyond that. Given this characterization, it is unsurprising that codetermination fails to significantly shift major outcomes like wages or investment...Importantly, recent codetermination proposals in the United States and United Kingdom mostly emulate existing codetermination laws, usually by proposing minority board-level representation. If limited power conveyed by minority board-level representation is key to explaining codetermination’s lack of impact, then we should expect the codetermination proposals in the US and UK to have similarly negligible impacts if implemented.

Codetermination may provide a durable institution that protects the democratic process from extreme corporate accumulations of wealth and power

A long-standing concern in American politics has been the destabilizing effect of large accumulations of wealth and power on the democratic process. Concentrated corporate wealth raises the risk that private corporations may wield outsized power, undermining democratic institutions.

Some see codetermination as a strategy for preserving democratic institutions within a landscape of rising corporate power. By allowing employees to elect a significant portion of corporate directors, codetermination can function similarly to the Constitutional separation of powers . Democratizing corporate decision-making may also democratize corporate speech, broadening the array of interests it represents.

There is nothing inherently undemocratic in corporate speech, unless corporations themselves are undemocratic...Citizens United recognized the corporate right to speak in the American public square. Currently, that poses a major problem for our democracy because corporations amplify the voices of a tiny number of the financial and managerial elite—the notorious 1 percent. If companies gave voice to a more diverse and pluralistic set of interests, the fact that corporations speak would not undermine democracy. On the contrary, corporate speech would reflect it.

The American people, Democrats and Republicans alike, want codetermination.

Recent polls suggest that codetermination enjoys bipartisan support. One nationally representative survey found that a majority of likely voters in every state—including Trump voters in all but four states—support codetermination . On the whole, 52% of likely U.S. voters reported supporting codetermination, while only 23% opposed it.

In 2020, prominent conservatives cosigned a statement in support of creating organized labor institutions, including codetermination, that give workers a “seat at the table .” Signatories included Marco Rubio (US senator), Jeff Sessions (former US attorney general), Oren Cass (executive director of American Compass), Jonathan Berry (former acting secretary for policy, US Department of Labor), and Richard Schubert (former chairman, National Job Corps Association).

But support for codetermination was not always widespread. In the 1970s, American unions generally opposed codetermination . But while Americans have a long, polarized history with unionization, relatively new policies like codetermination may carry less political baggage. Recent surveys suggest that applications of workplace democracy - including codetermination, employee stock ownership plans, and management elections - are less polarizing than unionization .

European managers, executives, and workers all report widely positive experiences with codetermination

In Sweden, 76% of corporate managing directors report positive experiences with codetermination. 81% of managing directors reported that it did not hinder effective decision-making , and only 5% reported that it had a negative impact on company activities .

Notably, the larger the company, the more likely the managing directors were to have positive views of codetermination.

In Germany, a 1998 commission unanimously concluded that codetermination deepened trust between management and labor , improving information flow. Anecdotally, the “overwhelming majority” of supervisory board decisions under German codetermination are unanimous .

Where implemented, codetermination has proven to be a remarkably stable institution.

Of the 14 European countries that implemented codetermination, only two—Hungary, and the Czech Republic—walked it back . Even so, Hungary retained codetermination for firms with two-tier boards (most firms in Hungary), and the Czech Republic, after abolishing mandatory codetermination in 2014, reintroduced the policy in 2017 for large firms with at least 5,000 employees.

Given the array of possible strategies a society could use to curb excessive corporate political power, corporations themselves might prefer codetermination over alternatives such as high corporate income tax rates, or rigorous antitrust regulation.

Advocates also suggest that codetermination could help a society weather unexpected shocks , such as COVID-19, by serving as a mechanism through which firms and employees could take coordinated action to mitigate worker/employer conflicts of interest.

Implementation

Although codetermination has only mild economic effects in Europe, this might be because many of the more likely effects had already been brought about by strong preexisting labor institutions. In the US, where labor institutions are significantly weaker, codetermination might have a stronger impact, whether positive or negative.

US corporate law is notably more flexible than European corporate law. Therefore, the implementation of any rigid, top-down mandate might have more pronounced consequences, especially on the rates of mergers, acquisitions, and buybacks.

The amount of power that codetermination grants workers, as well as the overall effects that codetermination might have on the economy, significantly depend on the portion of board seats to be held by worker representatives, and the scope of companies subject to the mandate.

The effects of codetermination might also significantly depend on the larger environment of organized labor institutions, or lack thereof. Related institutions, such as sectoral collective bargaining and union representation can both complement codetermination, and supply its practical infrastructure.

While Germany arguably reaps significant benefits from codetermination, legal, social, and institutional differences between Germany and the United States make it highly unlikely that the United States would be able to replicate those benefits. Furthermore, the costs of codetermination would probably be much higher in the United States than they are in Germany.

The lack of organized labor institutions in the US relative to Europe presents at least two challenges for implementing codetermination. First, the lack of other pro-worker channels suggests that codetermination may have greater economic effects , whether positive or negative. In 2015, only 7.2% of US private sector workers were covered under collective bargaining agreements, compared to 50.2% in Germany .

Second, the practical implementation of codetermination in Europe often relies integrally on elements of existing labor networks, such as the widespread presence of union representatives. Without such preexisting infrastructure, there is little precedent in the US for how the logistics of codetermination might actually work .

Proponents of economic democracy who seek to boost the bargaining power of workers could therefore consider—in addition to codetermination—implementing institutions such as stronger union representation or sectoral collective bargaining. Such institutions could not only complement codetermination, but also supply and develop its practical infrastructure .

Overall, much of the practical infrastructure of codetermination in European countries relies on the near-universal presence and widespread legitimacy of union representatives. There is therefore little precedent for how codetermination might be implemented in the United States, where many workplaces either lack union representatives entirely, or lack union representatives who hold the confidence of workers.

US corporate law is more flexible than European corporate law, and the American business environment is more active in mergers, acquisitions, and buybacks. A rigid, top-down mandate like codetermination might therefore have more pronounced consequences in the US.

Significant differences between US and European corporate law and business dynamics suggest that while codetermination fits well with the European ethos, it may cause more conflict when applied to the U.S.

US corporate law draws heavily on Delaware law, and is characterized by its flexibility and reliance on default rules (rules that apply in the absence of an agreement by relevant parties to be governed by a different rule). This is in contrast to German corporate law, which relies heavily on mandatory law.

This contrast leads to significantly differing business activities. Between 1981 and 2010, there were only 338 mergers in Germany . Over the same period in the US, there were 60,244. Similarly, between 1998 and 2014, Germany had 210 stock buybacks, compared to 11,096 in the US .

In Europe, evidence from Germany and Finland suggests that firms do not attempt to dodge codetermination mandates, such as by altering their business structures or reincorporating abroad. But concerns remain that, since US firms might have more to lose from being subjected to rigid mandates, such behavior may be more likely.

As a result, successfully implementing codetermination in the U.S. may require additional corporate governance laws , further reducing overall legal flexibility.

However, the costs of doing so [creating additional regulations to accommodate codetermination] would very likely be much greater in the United States than they are in Germany...German corporate law heavily relies on mandatory law anyway, so preventing corporate charters and bylaws from circumventing codetermination creates little or no extra costs. By contrast, for the United States, the enactment of additional mandatory corporate law norms means sacrificing at least in part one of its main benefits.

In Germany, codetermination arose from the bottom up as negotiated agreements between workers and employers. Only after widespread uptake did the federal government ratify codetermination as a mandate from above.

Such bottom-up implementation of codetermination could also be possible in the US. Currently, any group of employees in the U.S. could negotiate with their employer to immediately implement some form of codetermination. During their 2018 strike, Google employees demanded to have a worker-elected representative sitting on the board .